Academia Europaea elects KAUST plant microbiome visionary

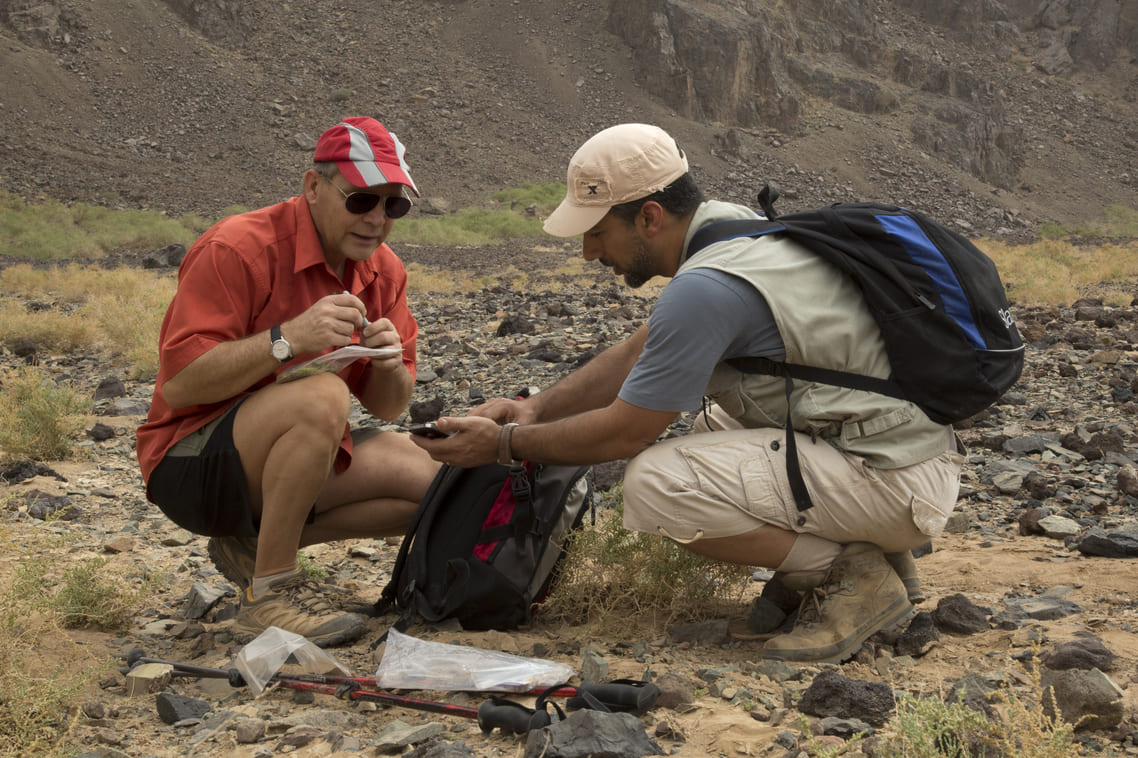

KAUST Professor Heribert Hirt (left) works in the field with a team member to study desert microbes and plant resilience.

In recognition of his pioneering research on the relationship between microbes and plant health, Professor Heribert Hirt, Plant Science, has been elected to the prestigious Academia Europaea — a pan-European academy that recognizes excellence in science, humanities, and letters. This distinction affirms both the global significance of his work, and the high caliber of research made possible at KAUST.

“This is a very high distinction — one that comes with obligations to do something for the general public and for the common good,” he said, adding that for KAUST, this honor from the European Academy of Sciences is a testament to the institutional support provided to him over the years. “For me, it reinforces the importance of translating scientific concepts and knowledge to the public.”

Hirt sees election to the Academia Europaea as a mark of prominence in his field — one that draws greater attention to his views and actions, elevates his visibility, and encourages broader engagement across the scientific community and beyond. “You become a sort of personalized feature of the scientific system.”

Joining KAUST in 2014, Hirt was drawn by the opportunity to study how plants survive extreme environmental stress — particularly in deserts, which he calls his “laboratory.” As a geneticist, he was intrigued by the possibility of uncovering natural, microbe-driven solutions to heat, drought, and salinity. Microbes are microscopic organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

Hirt’s research focuses on identifying microbial genes that benefit plants and finding local microbes worldwide with those functions. His work has shown that microbes are integral to plant life — even seeds carry them. Across millions of years, plants and microbes have co-evolved, forming a symbiotic relationship akin to the human gut microbiome. “In fact, this is also one of the sources for our human gut microbiome.”

Unfortunately, according to Hirt, modern chemically reliant agricultural practices harm the microbial life in soil that is essential for plants. Without these microbes, crops lose nutritional value, contributing to poor gastrointestinal health and widespread health issues for humans. “The solution is to replace the chemicals with microbial solutions. Microbes are the solution needed to protect the plants — and ultimately, to protect humans too.”

At KAUST, his work has led to the creation of a massive desert microbe biobank and proven how microbes can trigger protective responses to boost crop resilience. “We want to identify not only the microbes, but the mechanisms they use. From this knowledge, we can determine which microbes and which functions are good for human health.”

A unique journey

Born in Iran, raised in Germany, and educated in South Africa and Austria, Hirt followed a global path that reflects the broad perspective he brings to science. After earning a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from the University of Cape Town, he completed his master’s and Ph.D. in Vienna, followed by postdoctoral research in Vienna and Oxford.

His academic career has spanned multiple countries and leadership roles, including rising through Austria’s ranks, serving as a research director in Paris, and eventually joining KAUST. This international experience continues to shape his work and contributions to plant science on a worldwide scale. Amazingly, Hirt noted, plant science was not a field he envisioned pursuing early in his career — but it grew on him.

“I started by studying medicine. I wasn’t interested in treating humans, but I was interested in the molecular basis of diseases. So, I did a Ph.D. in human genetics. Then I realized that humans are poor subjects for genetics, because you can’t do experiments on them.”

After spending time in the United Kingdom working on yeast — a solid but, to him, boring genetic system — Hirt returned to Vienna, accepting a role in plant science. Though he initially knew little about plants, his expertise in genes, RNA, and proteins was just what the research team needed. Once he began the work, he quickly “fell in love with plants,” drawn to their beauty and versatility. “You can do any kind of experiment with them. They don’t complain.”

He added: “Eventually I reached the point of connecting plant health, microbes, and human health through the microbiome — it’s all connected. I’m quite happy that we could ‘close the circle,’ if you like.”

Communication matters

For Hirt, who leads PlantAct! — a think tank of plant science experts advancing agricultural solutions to climate change — clear communication is essential to achieving meaningful impact. He said scientists must learn to explain what they are doing and why it matters to non-scientists. His long-term goal is to make important but complex scientific concepts accessible to the general public, both in Saudi Arabia and globally.

“This is something that I think scientists are not doing enough. Some of the problems we’ve seen — skepticism of the public toward scientists — come from that. There’s this communication gap we must work on and bridge better if we want to continue doing really high-level science.”

Microbes play a vital role in supporting primary immune systems, he noted, making them essential to the health of both plants and animals, including humans. He believes advancing this understanding is key to holistic, healthy living. Fortunately, he sees growing awareness within the plant science community of its transformative potential. “We have to transform agriculture to produce healthy food, and not just empty, dead food.”

Hirt collaborates with Saudi ministries, NEOM, and others on desert reforestation and soil restoration. His KAUST team created a national soil bioatlas — a map that shows where different living organisms are found in a specific area. His team also launched GrowBioM, which offers data-driven, sustainable land use solutions.

Looking ahead, especially given his Academia Europaea election, Hirt hopes to further grow as a science communicator. “I want to help build bridges across scientific disciplines and between science and the general public.”