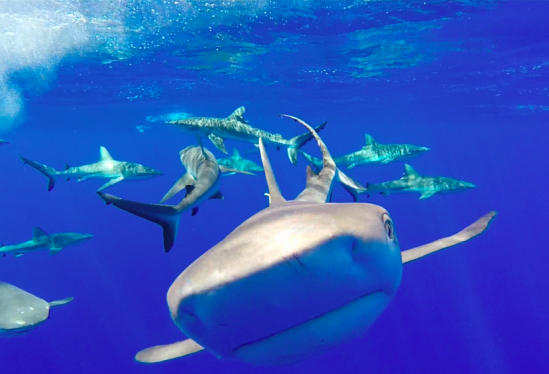

Global census reveals reef shark status, need for improved conservation management

Global FinPrint survey findings show that reef shark populations benefit from fisheries management, shark sanctuaries, and closed areas, but suffer in large human population areas with weak governance and overfishing. Photo: Courtesy of Global FinPrint.

In the 1940s global audiences watched spellbound upon seeing first-time film footage of marine life by Jacques-Yves Cousteau, famed French naval officer, underwater filmmaker, and inventor of scuba gear. Cousteau's ocean scenes brought the mysteries of the deep to the public eye, and in so doing, increased knowledge of marine species and habitats, and transformed the field of marine conservation.

Underwater documentation is an essential means of gathering marine data today. Methods continue to evolve. Marine scientists at KAUST participated in a landmark, visual census called Global FinPrint that turned cameras on reef sharks to assess the status of their populations around the world. Researchers gathered data using BRUVS—Baited Remote Underwater Video Systems.

The study's findings, published in the scientific journal Nature in July 2020, reveal that populations of reef sharks are thriving in locations where marine conservation policies and fishing regulations are in place, but scarce to none in areas where overfishing occurs and resource protections are poor.

Sharks were absent on nearly 20 percent of coral reefs surveyed where they should have been present. The Nature paper raised the idea of functional extinction—that a species may still be present in an ecosystem, but in such low numbers that it no longer serves its function.

Why reef sharks?

As apex predators at the top of the food web, reef sharks keep fish levels in check and maintain balance in the trophic chain, which can be important for reef recovery. They are "canary-in-the coal-mine" indicators about the overall condition of reef systems. To learn about reef sharks is to also learn about these other web-of-life connections. Yet these sharks are an understudied species.

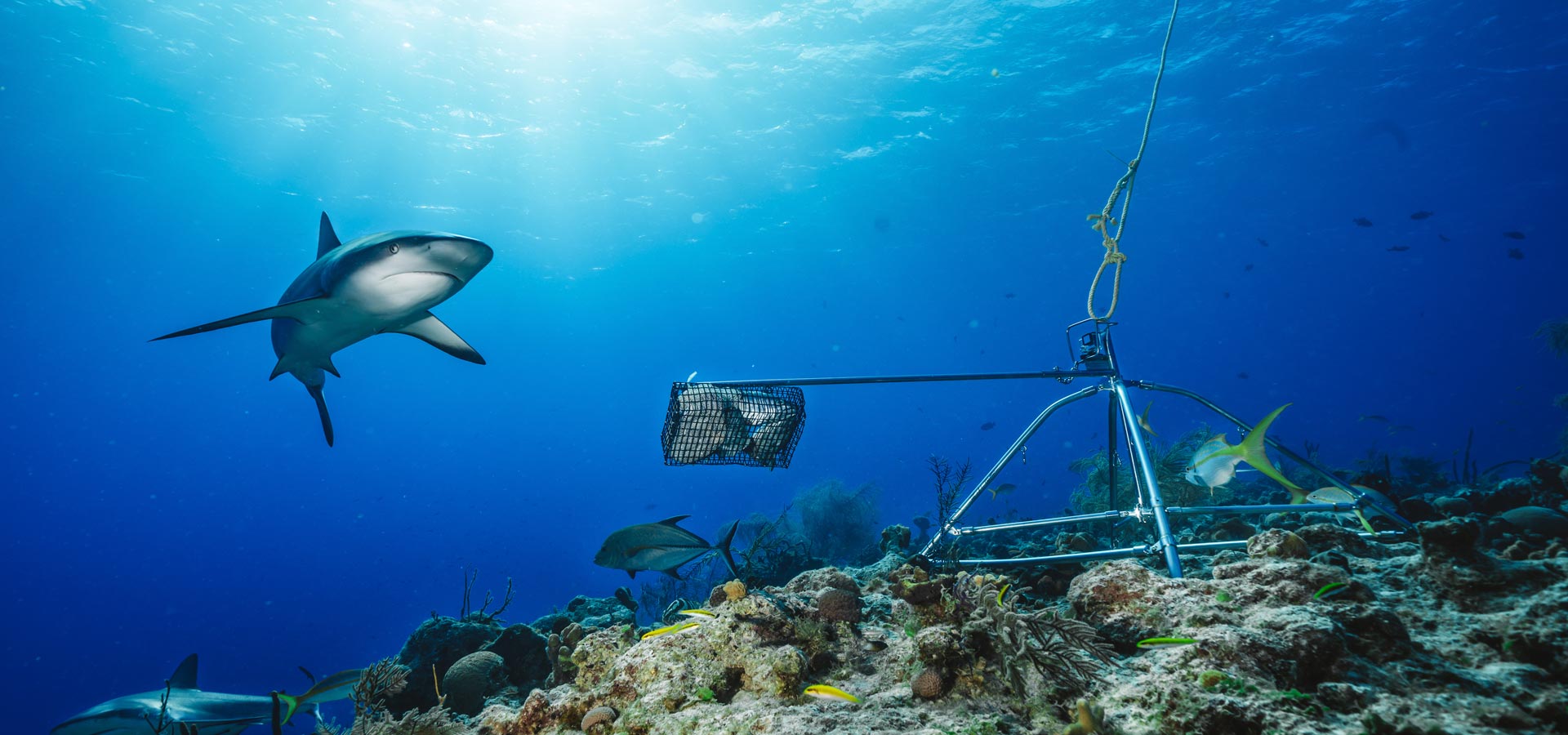

BRUVS footage shows a reef shark approaching bait in the Red Sea. Photo: Royale Hardenstine / KAUST.

One reason intensive sampling is needed in coral reefs is because these habitats are patchy by nature, with a high degree of flora and fauna variability. Reef sampling across the region helps to level out this variability for a greater region picture.

The method: Baited Remote Underwater Video Systems

BRUVS are underwater surveillance installations consisting of a simple camera like a Go Pro attached to an arm-like apparatus extending from a box of bait to lure sharks. The Global FinPrint set-up was designed to be low-tech and easily built with relatively common and cheap materials so that marine scientists anywhere could adapt the system to meet diverse budgets, travel circumstances, installation locations, and technical skills. Divers placed the equipment in a secure location on the sea floor, and then left the cameras unattended to record 60-minutes of marine life per survey session.

A shark investigates bait at a BRUVS installation in the Red Sea. Photo: Royale Hardenstine / KAUST

KAUST submitted data from 101 BRUVS drops in the Red Sea region of Saudi Arabia. With 58 countries and territories participating, 15,000 individual surveys contributed more than 20,000 hours of footage gathered from 400 reefs around the world. Teams of scientists and volunteers reviewed the footage, counting and identifying every shark and other species that entered the frame.

Portrait of Dr. Michael Berumen, director of the Red Sea Research Center at KAUST. Photo: KAUST.

Although BRUVS are not new to marine science, the scale of this study is unprecedented. Collaborators in this project applied the same installation, recording, and annotation protocol to their local BRUVS surveys to ensure that results could be compared from around the world.

Dr. Michael Berumen, marine scientist and director of the Red Sea Research Center at KAUST, commented on the significance of Global FinPrint.

"I'm not aware of any study on reef sharks that's put together so much data from so many places with a standardized common approach," he said.

"We couldn't get that scope of data working individually. The model is a powerful means of helping people understand ocean phenomena and pressures occurring on a global scale, and will be increasingly useful for future research collaborations. The information can then be used to improve marine management strategies on local scales."

The Red Sea survey

The Saudi Red Sea region was the only location that contributed data from the Red Sea. It is also among the places surveyed where reef shark numbers were much lower than expected.

Marine biologist Royale Hardenstine, a KAUST doctoral student in the Reef Ecology Lab, helped coordinate the KAUST BRUVS surveys. Global FinPrint required that units be placed in both fished and unfished locations to get a balanced span of low to high reef shark populations and show which places were doing well compared to the rest of the region. She chose locations offshore KAUST "to survey our home base and know what's going on here" and also reefs near Al Lith, an area regularly surveyed by KAUST scientists that is located further south in the Red Sea.

Sciencetown episode on reef sharks

Listen to Berumen, Hardenstine and their co-authors talk about the research in episode 15 of Sciencetown - BRUVS watching reef sharks

"Unfortunately, the Saudi Arabian coast has very few marine protected areas, and the ones that do exist are rarely enforced, so there is no good place to go where there's no fishing pressure," Hardenstine said.

"Instead, I tried to get a gradient across the shelf, hoping that the reefs and islands far offshore would have less fishing pressure because they are more difficult to get to."

Hardenstine said she also included reefs previously surveyed by Dr. Julia Spaet, a former marine biologist in the Reef Ecology Lab at KAUST who had previously raised alarm bells about diminishing reef shark populations in the Red Sea. Spaet also used BRUVS to gather data for her projects (predating the Global FinPrint study) and surveyed local fish markets to see what sharks and other species were being sold there.

Marine biologist and KAUST doctoral student Royale Hardenstine prepares for a dive in the Red Sea. Photo: Courtesy Lyndsey Tanabe.

An avid shark fan and diver, Hardenstine said it took six or seven months before she saw her first shark in the Red Sea, even with regular diving, and that she's seen more tiger sharks in Saudi fish markets than the sea.

She reminisced about places she has visited where sharks were abundant, like Tahiti in French Polynesia, where she observed a total of seven species of sharks in one dive "without even trying." These included tiger sharks, black tip reef sharks, lemon sharks, and nurse sharks.

She noted that countries that capitalize on dive tourism experience ecological as well as economic benefits. People want to swim with sharks and see beautiful coral reefs, and reef ecosystems enjoy a measure of protection in places that prioritize dive activities. Such is the case with Sudan, located on the western side of the Red Sea across from Saudi Arabia. Sudan is a hugely popular dive destination for hammerhead sharks, and its shark populations are thriving.

What accounts for low shark numbers in the Saudi Red Sea region, and absent numbers in 20% of the other places surveyed? Berumen said a variety of factors contribute.

"Overfishing is a problem in certain parts of the world where there is direct, targeted fishing for sharks. In other places, shark deterrents like nets in recreational swimming or bathing areas can impact their populations."

He said effects could also be indirect.

"It may be that fishing is not targeting sharks but the food that sharks eat. And if you remove all the potential prey for sharks, you are eventually going to see an impact on the sharks, themselves, even if you never directly go after a single shark."

Both Berumen and Hardenstine emphasized the need for local knowledge to understand the particular problems in each region, and what could be done to alleviate those stressors and help rebuild shark populations.

Hardenstine reflected, "And if we're at the point of functional extinction, then now is the time to pay attention in order for things to change."

Sharks, sharks and more sharks

Illustration circa 1500s of a sea monster eating a sailor in the Mediterranean Sea. Photo: British Library of Maps.

Dr. Yannis Papastamatiou, a marine biologist and shark expert at Florida International University, gathered BRUVS data at Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, a marine protected, coral atoll composed of islets, reef and lagoons in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and American Samoa.

Marine biologist Yannis Papastamatiou contributed Global FinPrint BRUVS data from Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: Courtesy Yannis Papastamatiou.

He said it's commonly assumed that "sea monsters" refers to sharks, and that such historical descriptions, as well as old photographs and other records, can help scientists infer what populations of species could have been like a long time ago.

"We only started surveying with modern scientific methods recently, long after the effects of fishing were felt," he said.

"It's incredible to think that there must have been a lot of sharks in Greek waters thousands of years ago. I come from Greece, and the chance of seeing a shark in the Mediterranean today is pretty low. In fact, in all my time diving there, I've never seen a shark."

Aerial view of Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, a healthy refuge for reef sharks and other marine species. Photo: Kydd Pollock / US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The atoll is the largest marine protected area in the world. Managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, it has been unoccupied and closed to fishing for more than 20 years. The refuge shows what an unfished system without human impacts looks like, and that ecosystems will flourish when left undisturbed.

Marine ecologist Darcy Bradley coordinated BRUVS surveys from Palmyra Atoll National Marine Refuge. Photo: Courtesy Darcy Bradley.

Marine ecologist Darcy Bradley, co-director of the Sustainable Fisheries Group at University of California, Santa Barbara, coordinated the BRUVS survey for Palmyra Atoll. Her team contributed 25 surveys, each at 60-minutes.

"We had the great privilege of surveying one of the most undisturbed, pristine coral reef ecosystems on our planet," she said.

"Reviewing footage from Palmyra Atoll was so much fun, because we witnessed coral reefs that were full of life and filled with sharks and other predators like jacks, groupers and snapper. The maximum number of reef sharks we saw together in one video frame was around four or five individuals. Imagine this many individual sharks, each one approximately five feet long, together in one space. That's a lot of reef sharks!"

A curious reef shark investigates a camera in Palmyra Atoll National Marine Refuge. Photo: Courtesy Darcy Bradley.

Given the unspoiled nature of Palmyra Atoll, the island provides an ecological baseline for envisioning how conservation strategies could improve other reef ecosystems.

Papastamatiou said this will require "careful research into the spatial ecology of these animals, and what areas they need to use." He emphasized a need for conservation approaches based on quality of habitat, not quantity of places to protect, because not all habitat areas are beneficial to or used by sharks.

Outside protected borders

One challenge to shark conservation is that sharks can be both site attached and mobile, meaning they don't all stay in one reef ecosystem. Some are transient, and cross outside human designated borders. For many species, waters in one area are the same as waters in another in terms of their movements and usage. Yet fishing practices and policy management in these areas can vary significantly, which can have a huge influence over the abundance and biodiversity of shark species.

Shedd Aquarium in Chicago contributed data to Global FinPrint from the Bahamas, where they have been conducting research for the past three decades. Dr. Steven Kessel, director of marine research at Shedd, discussed the consequences of mobility for some shark species. For example, Caribbean reef sharks in the Bahamas are site attached, but tiger sharks spend only a portion of their time there.

Dr. Steven Kessel, director of marine research at Shedd Aquarium, Chicago. Photo: Courtesy Steven Kessel.

"Many tiger sharks swim out to the mid-Atlantic, where they are susceptible to high sea fisheries. If they cross into Florida waters, they are regulated by the National Marine Fisheries Service—it's illegal to fish them there—but they can be harvested in other parts of the US, and if they move into the broader Caribbean, they can be taken at certain times of the year."

He said sharks are abundant in the Bahamas, yet scarce in Jamaica, even though the two countries are in close proximity to each other. He attributed healthy shark populations in the Bahamas to the country's progressive conservation measures. In 1993 the Bahamas banned the use of commercial long lines and gill nets—incredibly destructive fishing methods known to kill sharks—and in 2011 it designated its entire waters (approx. 630,000 sq. km) as a shark sanctuary.

"It is illegal to kill sharks anywhere within that large expanse of ocean, so it's a real safe haven for sharks," he said.

A Caribbean reef shark passes a BRUVS in the Bahamas. Photo: Courtesy Amy Mann.

"We have the ability to be better and to use science and technology to improve our practices as a species, to minimize our effect on the planet, and work more in harmony on behalf of the planet and animals. But that's only going to happen by high-level collaboration and coordination between our efforts, otherwise we are just working against each other, and we're not going to get ahead of the problem."

Related stories

-

Chasing Whale Sharks

- Whale Shark hot spot offers new conservation insights

-

Global FinPrint Instagram